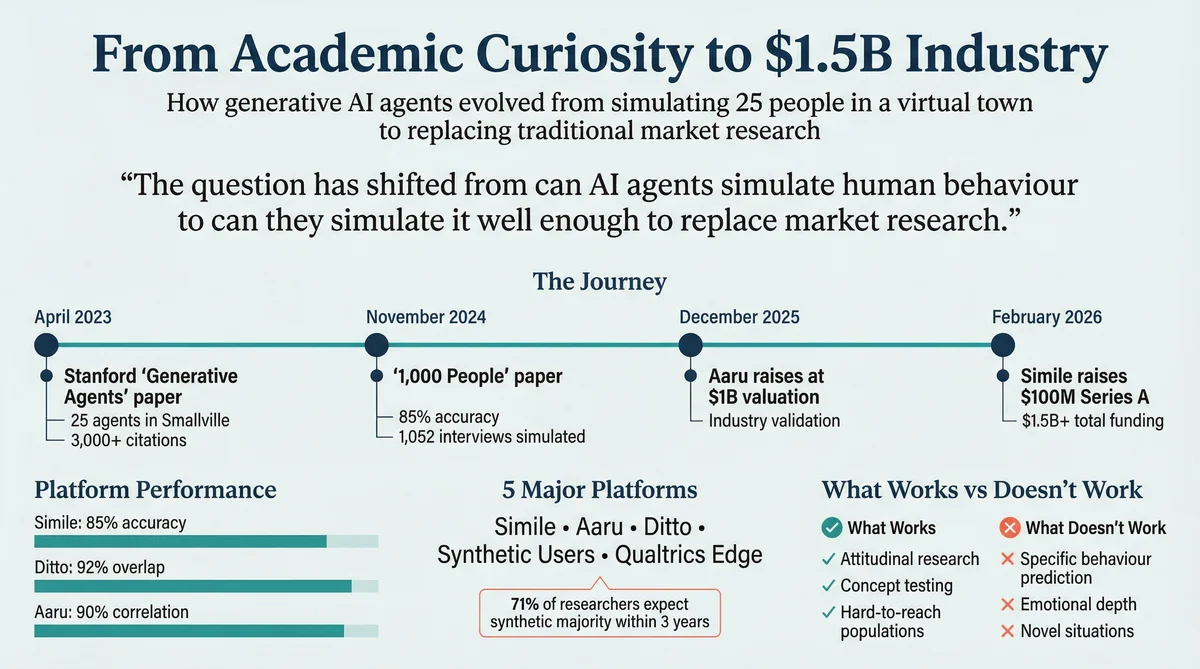

In April 2023, a group of Stanford researchers published a paper that placed 25 AI agents in a virtual town and watched what happened. The agents threw parties, formed friendships, coordinated activities, and generally behaved like a particularly wholesome episode of The Sims. The paper, "Generative Agents: Interactive Simulacra of Human Behavior," has since been cited over 3,000 times and spawned at least three venture-backed companies with combined valuations exceeding $2 billion.

Three years on, the question has shifted from "can AI agents simulate human behaviour?" to "can they simulate it well enough to replace traditional market research?" The answer, depending on whom you ask, ranges from "absolutely, this changes everything" to "this is the homeopathy of market research." The truth, inevitably, is more nuanced than either position.

This article traces the journey from academic curiosity to commercial product, examines what the technology can and cannot do, and assesses where generative agents fit in the future of market research.

The Paper That Started It All

The original generative agents paper by Joon Sung Park, Joseph O'Brien, Carrie Jun Cai, Meredith Ringel Morris, Percy Liang, and Michael S. Bernstein introduced an architecture with three key components:

Memory stream: A comprehensive record of each agent's experiences, stored as natural language descriptions with timestamps. The agent remembers what it has done, seen, and been told.

Reflection: A process that periodically synthesises memories into higher-level observations. An agent might remember attending three parties and reflect that "I enjoy social gatherings." This mirrors how humans form generalised beliefs from specific experiences.

Planning: Agents generate multi-step action plans based on their memories and reflections, then recursively decompose these plans into moment-by-moment actions.

The researchers placed 25 agents in a virtual environment called Smallville, each with a unique personality and backstory. They initialised one agent (Isabella Rodriguez) with the goal of organising a Valentine's Day party. What followed was genuinely startling.

Without being programmed to do so, agents autonomously:

Spread party invitations through social networks

Formed new relationships based on shared interests

Asked each other on dates to the party

Navigated conflicting social obligations

Arrived at the right location at the right time

The behaviours were emergent, meaning they arose from the interaction of the architecture's components rather than being explicitly programmed. This was the result that captured imaginations: not just that AI could answer questions, but that it could behave.

From 25 Agents to 1,000 People

The follow-up paper, "Generative Agent Simulations of 1,000 People" (November 2024), addressed the obvious question: can you do this at scale, with agents that represent real individuals rather than fictional characters?

The researchers conducted two-hour qualitative interviews with 1,052 real people about their lives, values, preferences, and decision-making processes. They used these interviews to train individual AI agents for each participant.

The validation methodology was straightforward: give the AI agents the same General Social Survey (GSS) questions that the real participants had answered, and compare results. The key finding:

"The generative agents replicated participants' responses on the GSS with 85% of the accuracy that participants achieved when retaking the survey themselves two weeks later."

The 85% benchmark is important because human test-retest reliability itself isn't 100%. People don't give identical answers when retaking a survey two weeks later; attitudes shift, moods change, questions are interpreted differently. By measuring AI accuracy against human self-consistency rather than perfect replication, the researchers set a more meaningful bar.

The paper also found that agents were better at predicting some response types than others. Factual questions about behaviour ("Did you vote in the last election?") were replicated more accurately than subjective evaluations ("How satisfied are you with your life?"). This makes intuitive sense: factual recall is more stable than emotional assessment.

The Commercial Landscape: Who's Selling Generative Agents?

The journey from academic paper to enterprise product has been remarkably fast. In under three years, at least five significant companies have launched products based on some form of generative agent or synthetic respondent technology:

Simile ($100M, February 2026)

The most direct commercialisation of the Stanford research. Founded by Joon Sung Park, Michael Bernstein, Percy Liang, and Lainie Yallen. Simile uses the interview-trained agent architecture from the 1,000 People paper, with a partnership with Gallup for nationally representative panels. Customers include CVS Health, Telstra, and Suntory. Enterprise-only pricing, estimated $100,000+/year.

Aaru ($1B Valuation, December 2025)

The market's other heavyweight, backed by Redpoint Ventures. Aaru's agents helped EY recreate their annual Global Wealth Research Report in a single day with 90% median correlation to the original six-month study. Also predicted the New York Democratic primary outcome. Focused primarily on financial services, consulting, and public opinion research.

Ditto (Population-Grounded Personas)

Ditto takes a different architectural approach, building synthetic personas grounded in population-level data rather than individual interviews. The platform offers 300,000+ personas across 50+ countries, with published 92% overlap with traditional focus groups. Self-serve access at $50,000-$75,000/year with unlimited studies, plus integrations with Figma, Canva, and Framer for design feedback.

Synthetic Users (UX-Focused)

Positioned for product and design teams rather than market researchers. Synthetic Users creates detailed individual personas for open-ended UX research conversations at $2-$27 per respondent. The conversational interface supports probing, follow-up questions, and exploratory research that traditional surveys can't support.

Qualtrics Edge Audiences (Survey Augmentation)

The establishment's response. Qualtrics has embedded "scientifically validated synthetic respondents" into its survey platform, backed by 25+ years of accumulated research data. This isn't a standalone product but an enhancement to the world's most widely used survey tool, making synthetic research a toggle rather than a new vendor.

What Generative Agents Can and Cannot Do for Market Research

What Works Well

Attitudinal research: Understanding how population segments feel about topics, brands, or issues. The 85-92% accuracy range reported by leading platforms is strong enough for directional insights, particularly at the aggregate level.

Concept testing at speed: Testing product concepts, messaging variations, and positioning options in minutes rather than weeks. The speed enables iterative testing that traditional research can't support.

Hard-to-reach populations: Simulating responses from demographics that are expensive or impossible to recruit traditionally: rural elderly, ultra-high-net-worth individuals, niche professional segments, populations in conflict zones.

Hypothesis generation: Identifying patterns and themes to explore in subsequent traditional research. Using synthetic panels to narrow the research questions before investing in human panels.

Competitive benchmarking: Understanding how your brand compares to competitors in the minds of synthetic consumers. Not definitive, but faster and cheaper than tracking studies for directional intelligence.

What Doesn't Work (Yet)

Predicting specific behaviours: Knowing that synthetic consumers "prefer" Product A over Product B doesn't reliably predict actual purchase decisions. The gap between stated preference and revealed behaviour is well-documented in human respondents and is likely amplified in synthetic ones.

Emotional depth: AI agents can report that they "feel excited" about a product, but this is a linguistic pattern, not an emotional experience. For research that depends on genuine emotional response (advertising pre-testing, sensory evaluation, experience design), synthetic agents remain limited.

Novel situations: Generative agents are trained on historical data. Their predictions about truly novel products, categories, or behaviours are extrapolations from existing patterns. The further a research question departs from the training distribution, the less reliable the predictions.

Cultural nuance: Population-level calibration captures broad cultural patterns but may miss subcultural dynamics, emerging trends, or context-dependent behaviour that hasn't yet appeared in training data.

Regulatory-grade evidence: No major regulatory body currently accepts synthetic research as evidence for product claims, pharmaceutical efficacy, or financial suitability. This may change, but it hasn't yet.

The Sceptics' Case

Not everyone is convinced. Conjointly, a traditional research platform, published a provocative critique calling synthetic respondents "the homeopathy of market research." Their argument: synthetic agents don't actually experience products, don't have real preferences, and don't make real decisions. What they produce is a statistical echo of past survey responses, dressed up as genuine consumer insight.

This criticism has merit. There is a genuine epistemological question about whether a language model's output constitutes "insight" in the same way that a human respondent's answer does. When a synthetic agent says it prefers Brand A, it's generating a statistically plausible response, not expressing a genuine preference.

But the criticism also misses the practical point. Nobody in the synthetic research industry (the serious players, at least) claims that AI agents are conscious consumers with real preferences. The claim is narrower and more defensible: that synthetic panels can predict the distribution of human responses with sufficient accuracy to inform business decisions. You don't need each individual synthetic response to be "real." You need the aggregate pattern to be useful.

The honest assessment is that both the optimists and the sceptics are partly right. Generative agents are not a replacement for all traditional research. They are a genuinely useful supplement that can answer certain types of questions faster, cheaper, and at greater scale than previously possible. The skill is knowing which questions they can answer well.

What the Industry Thinks

Despite the criticism, industry adoption signals are strong:

71% of market researchers surveyed by Qualtrics expect synthetic responses to constitute the majority of market research within three years. This isn't a fringe view; it's the mainstream expectation.

a16z (Andreessen Horowitz) has declared synthetic research "a new era of instant insight," with significant investment interest across their portfolio.

Combined funding in the synthetic research space now exceeds $1.5 billion, with Simile ($100M), Aaru ($1B+ valuation), and multiple smaller players attracting significant capital.

Enterprise adoption is accelerating: CVS Health (Simile), EY (Aaru), and major CPG brands (Ditto) are running production studies, not just pilots.

The trajectory is clear, even if the destination is still uncertain. The question is no longer "will synthetic research become mainstream?" but "how quickly, and in which use cases first?"

Where This Is Going: Three Predictions

1. Hybrid Models Will Win

The future is not "synthetic OR traditional" but "synthetic AND traditional." The most valuable workflow will use synthetic panels for rapid hypothesis testing and iteration, then validate critical findings with traditional research before major decisions. Platforms that make this hybrid workflow seamless (Qualtrics Edge is an early example) will capture the largest market share.

2. Validation Standards Will Emerge

The market currently lacks agreed standards for measuring synthetic research accuracy. Every platform uses different benchmarks, different methodologies, and different claims. Within two years, expect industry bodies (ESOMAR, MRS, or equivalent) to publish validation frameworks that allow apples-to-apples comparison. This will benefit platforms with strong validation (Ditto's 50+ parallel studies, Simile's peer-reviewed findings) and expose those that have been trading on hype.

3. The Price Will Fall

As competition intensifies and the technology commoditises, expect synthetic research pricing to fall significantly. Today's enterprise tier ($100,000+) will become tomorrow's professional tier. Self-serve access will become the norm, not the exception. The platforms that survive will be those that build defensible advantages in data, integrations, and accuracy rather than relying on pricing opacity.

A Practical Guide for Getting Started

If you're convinced that generative agents have a role in your research workflow, here's how to start without overcommitting:

Pick a known question. Run a synthetic study on a topic where you already have traditional research data. Compare the results. This gives you a personal validation baseline that's more meaningful than any platform's published accuracy metric.

Start with directional research. Use synthetic panels for questions where "roughly right" is good enough: early concept testing, competitive positioning, message testing. Save traditional research for high-stakes decisions where precision matters.

Use self-serve first. Platforms like Ditto and Synthetic Users let you run studies immediately without enterprise commitments. Build experience and confidence before signing annual contracts.

Document what works. Keep a log of which research questions produce useful synthetic insights and which don't. Over time, you'll develop institutional knowledge about where generative agents add value for your specific use cases.

Stay sceptical but open. The technology is real, the limitations are real, and the commercial hype is real. Treat synthetic research as a powerful new tool, not a magic oracle. The organisations that develop nuanced judgement about when to use it will get the most value.

The Bottom Line

The journey from Smallville to CVS has been remarkably fast. In under three years, generative agents have gone from a novel academic concept to a $1.5 billion+ commercial category with Fortune 500 customers and serious enterprise adoption. The technology works well enough for certain use cases to be genuinely valuable today, while remaining limited enough for others to require caution.

The next three years will likely see validation standards emerge, prices fall, and hybrid synthetic-traditional workflows become standard practice. Early adopters who start building institutional knowledge now will have a significant advantage when the mainstream catches up.

Whether you start with Simile's enterprise-grade agents, Ditto's self-serve personas, or Synthetic Users' UX interviews, the most important step is the first one. Run a study. Compare the results. Form your own view. The generative agents have already left the lab. The question is whether your research programme will meet them.

Phillip Gales is co-founder at Ditto, a synthetic market research platform. He has no financial relationship with Simile, Aaru, Synthetic Users, SYMAR, or Qualtrics.