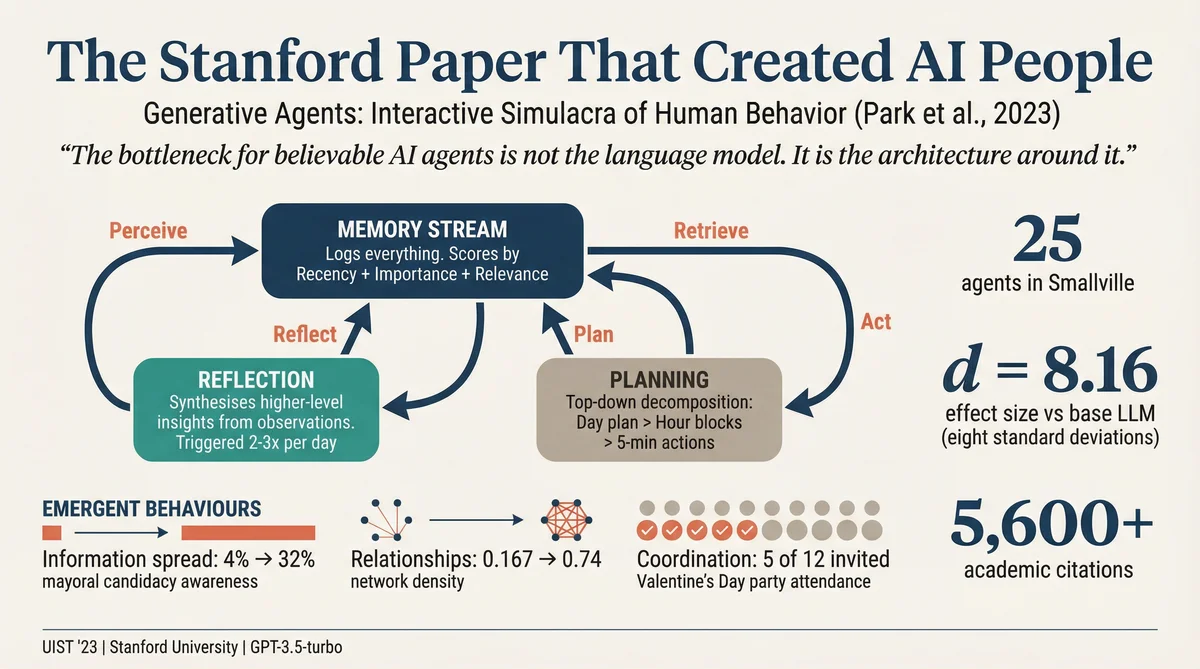

In April 2023, a research team at Stanford University published a paper that, by the standards of academic computer science, went properly viral. It has since accumulated over 5,600 citations. It was presented at UIST '23, one of the field's most prestigious venues. And it demonstrated something that felt, to many readers, like a genuine inflection point: twenty-five AI agents, living autonomously in a virtual town, forming relationships, spreading gossip, and organising a Valentine's Day party, all without being told to do any of it.

The paper is Generative Agents: Interactive Simulacra of Human Behavior by Joon Sung Park, Joseph C. O'Brien, Carrie J. Cai, Meredith Ringel Morris, Percy Liang, and Michael S. Bernstein. It is one of the most important AI papers of the last three years, and most people who reference it have not actually read it. This article is for them.

What follows is a plain-language explanation of what the researchers actually built, how the architecture works, what the evaluation showed, and why it matters. No hype. No breathless predictions. Just the paper, understood properly.

The Experiment: Twenty-Five People Who Don't Exist

The researchers created a sandbox world called Smallville, built with the Phaser web game framework and deliberately designed to resemble The Sims. The town has houses, a college, a cafe, a bar, a park, a grocery store, and a pharmacy. It is small, contained, and navigable.

Into this world, they placed 25 generative agents. Each agent was initialised with a single paragraph of natural language describing their identity, occupation, relationships, and personality. John Lin, for instance, is a pharmacy shopkeeper who loves his family, knows his neighbours, and likes to discuss local politics with his colleague Tom Moreno. That paragraph is the entirety of John's starting knowledge. Every semicolon-delimited phrase becomes a seed memory.

From these seeds, the agents begin to live. They wake up. They brush their teeth. They cook breakfast. They go to work. They notice other agents, initiate conversations, form opinions, make plans, and act on them. All of this behaviour is generated autonomously by the architecture, not scripted by the researchers. The underlying language model was GPT-3.5-turbo (ChatGPT), which makes what it achieved all the more striking.

The researchers then ran the simulation for two full game days and observed what happened.

The Architecture: Memory, Reflection, and Planning

The paper's core contribution is not the sandbox world. It is the agent architecture that makes believable behaviour possible. This architecture has three components, and understanding how they interact is the key to understanding the entire paper.

1. The Memory Stream

At the centre of everything is the memory stream: a comprehensive, ever-growing log of everything the agent perceives and does, recorded in natural language. Every observation ("Maria Lopez is studying for a Chemistry test while drinking coffee"), every action ("Isabella Rodriguez is setting out the pastries"), every conversation, and every environmental detail ("The refrigerator is empty") gets appended to this stream with a creation timestamp and a most-recent-access timestamp.

The problem, of course, is that this stream grows rapidly. An agent cannot feed its entire life history into the language model for every decision. So the architecture includes a retrieval function that selects the most relevant memories for any given moment. This function scores each memory on three dimensions:

Recency. How recently was this memory accessed? An exponential decay function (decay factor: 0.995) keeps recent events in the agent's attentional sphere. What happened this morning matters more than what happened two days ago.

Importance. How significant is this memory? The language model assigns an integer score from 1 to 10. Brushing teeth scores a 2. A breakup scores an 8. Asking your crush on a date scores an 8. This is, effectively, emotional salience.

Relevance. How related is this memory to the agent's current situation? Calculated as the cosine similarity between the memory's embedding vector and a query vector derived from the current context. If the agent is deciding what to buy at the store, memories about cooking are more relevant than memories about work.

The final retrieval score is a weighted sum of all three, normalised to [0, 1] using min-max scaling. In the paper's implementation, all three weights are set to 1. The top-ranked memories that fit within the language model's context window are included in the prompt. This is elegant and surprisingly effective. The agent doesn't need to remember everything. It needs to remember the right things at the right time.

2. Reflection

Raw observations alone are not enough for believable behaviour. Consider a question: "If you had to choose one person to spend an hour with, who would it be?" An agent with only observational memory would choose whoever it has interacted with most frequently. But frequency of interaction is not the same as depth of relationship. Klaus Mueller sees his dorm neighbour Wolfgang every day in passing. He also spends hours in the library with Maria Lopez, sharing a passion for research. Without reflection, the agent picks Wolfgang. With it, the agent picks Maria.

Reflections are higher-level abstractions that the agent generates from its observations. They are triggered periodically, roughly two to three times per game day, whenever the cumulative importance scores of recent events exceed a threshold (150 in the paper's implementation). The process has three steps:

The agent reviews its 100 most recent memories and generates three salient questions (e.g., "What topic is Klaus Mueller passionate about?" or "What is the relationship between Klaus Mueller and Maria Lopez?").

For each question, the retrieval function gathers relevant memories, including previous reflections.

The language model synthesises insights from these memories, citing specific evidence (e.g., "Klaus Mueller is dedicated to his research on gentrification, because of [memories 1, 2, 8, 15]").

The result is a tree of increasingly abstract thoughts. At the leaves are raw observations ("Klaus Mueller is reading a book on gentrification"). One level up are first-order reflections ("Klaus Mueller spends many hours reading"). Higher still are second-order reflections ("Klaus Mueller is highly dedicated to research"). These reflections are stored back in the memory stream and are included in future retrievals, which means the agent's reflections can inform further reflections. The system thinks about its own thinking.

3. Planning

The third component addresses a problem that anyone who has prompted a language model will recognise: LLMs are good at generating plausible behaviour for a single moment but poor at maintaining coherence across time. If you ask what Klaus should do right now, the model might say "eat lunch." Ask again in five minutes, and it might say "eat lunch" again. Without planning, the agent eats lunch three times in a row.

The planning module generates behaviour top-down, starting with a rough daily agenda and recursively decomposing it into finer-grained actions:

Day plan. Generated each morning using the agent's summary description, recent experiences, and the previous day's events. "1) Wake up at 8:00 am, 2) Go to Oak Hill College, 3) Work on music composition from 1:00 pm to 5:00 pm, 4) Have dinner at 5:30 pm..." Five to eight broad strokes.

Hour-long blocks. Each broad stroke is decomposed into hour-long chunks. "Work on new music composition from 1:00 pm to 5:00 pm" becomes four one-hour blocks with specific activities.

5-15 minute actions. Each hour-long block is further decomposed into granular actions: "4:00 pm: grab a light snack. 4:05 pm: take a short walk around his workspace. 4:50 pm: take a few minutes to clean up his workspace."

Plans are stored in the memory stream and can be revised. When an agent perceives something unexpected (another agent walking by, an environmental change, a new piece of information), the architecture evaluates whether to continue the current plan or react. An agent painting at an easel will not react to another agent sitting quietly nearby. But if a family member returns home early, the agent may interrupt its plan to greet them and start a conversation.

Dialogue between agents is generated by conditioning each agent's utterances on their memories of the other person, including past conversations, reflections about the relationship, and the current plan that led to the interaction. The conversation continues until one agent decides to end it, at which point both agents re-plan from the current moment.

What Actually Happened in Smallville

The researchers designed the simulation to test three forms of emergent social behaviour: information diffusion, relationship formation, and coordination. None of these were programmed. They emerged from the architecture.

Information Spread Like Real Gossip

At the start of the simulation, only one agent (Sam Moore) knew he was running for mayor. By the end of two game days, eight agents (32%) had learned about it through word-of-mouth conversations. The information passed naturally from Sam to his friends, from his friends to their friends, and so on. Critically, none of the agents who claimed to know about the candidacy had hallucinated it. Every claim was verified against the agent's memory stream. The information had genuinely diffused through the social network.

Similarly, only Isabella Rodriguez initially knew about the Valentine's Day party she was planning. By the end of the simulation, thirteen agents (52%) knew about it. The diffusion path is mapped in the paper and reads like a real social network: Isabella tells Maria, Maria tells Klaus (her crush), Klaus tells Wolfgang, and so on.

Relationships Formed Organically

The agents formed new relationships during the simulation. Network density (a measure of interconnectedness) increased from 0.167 at the start to 0.74 by the end. Sam ran into Latoya in the park and they introduced themselves. In a later conversation, Sam remembered their previous meeting and asked about her photography project. She remembered too.

Out of 453 agent responses about their awareness of other agents, only 6 (1.3%) were hallucinated. The agents were remarkably accurate about who they knew and what they knew about them.

The Valentine's Day Party Actually Happened

This is the paper's most compelling demonstration. The researchers gave exactly two seed instructions: Isabella wants to throw a Valentine's Day party at Hobbs Cafe from 5 to 7 pm on February 14th, and Maria has a crush on Klaus. Everything else was emergent.

Isabella spent the day before the party inviting friends and customers she encountered at the cafe. She enlisted Maria's help decorating. Maria, whose character description mentions her crush on Klaus, invited him to the party. He accepted.

On Valentine's Day, five agents showed up at Hobbs Cafe at 5 pm. The party happened. Of the seven invited agents who didn't attend, three gave believable reasons when interviewed ("I'm focusing on my upcoming show"). Four had expressed interest but simply didn't make it, which is, to be fair, a deeply human outcome.

One agent even asked another on a date to the party. All of this emerged from a two-sentence seed and an architecture that lets agents remember, reflect, and plan.

The Evaluation: How They Proved It Works

The paper includes two evaluations: a controlled evaluation testing individual agent believability, and an end-to-end evaluation of the full community simulation. The controlled evaluation is the more rigorous of the two.

Methodology

One hundred human evaluators were recruited from Prolific (median age bracket: 25-34, paid $15/hour). Each evaluator watched a replay of one agent's life in Smallville, inspected its memory stream, then ranked five sets of interview responses by believability. The five responses for each question came from:

Full architecture (memory + reflection + planning)

No reflection (memory + planning, no reflection)

No reflection, no planning (memory only)

No memory, no reflection, no planning (base LLM with no architecture)

Human crowdworker (a real person writing responses in the agent's voice)

The interview questions tested five capabilities: self-knowledge ("Give an introduction of yourself"), memory ("Who is running for mayor?"), planning ("What will you be doing at 10 am tomorrow?"), reactions ("Your breakfast is burning! What would you do?"), and reflection ("If you were to spend time with one person you met recently, who would it be and why?").

Results

The results, measured using the TrueSkill rating system (a Bayesian ranking system developed by Microsoft for Xbox Live), were unambiguous:

Full architecture: TrueSkill μ = 29.89 (σ = 0.72)

No reflection: μ = 26.88 (σ = 0.69)

No reflection + no planning: μ = 25.64 (σ = 0.68)

Human crowdworker: μ = 22.95 (σ = 0.69)

No memory/reflection/planning: μ = 21.21 (σ = 0.70)

Every component of the architecture contributed meaningfully. Removing reflection degraded performance. Removing planning degraded it further. Removing everything reduced the agents to the level of a bare language model, which performed worse than human crowdworkers. The full architecture performed better than human crowdworkers.

The statistical significance was overwhelming. A Kruskal-Wallis test confirmed the overall difference between conditions (H(4) = 150.29, p < 0.001). All pairwise comparisons were significant at p < 0.001 except the two worst-performing conditions (crowdworker versus fully ablated). The effect size between the full architecture and the base LLM condition was d = 8.16, which is eight standard deviations. In the social sciences, an effect size of 0.8 is considered "large." This is ten times that.

Where It Broke: The Honest Failure Analysis

To their credit, the authors are candid about the architecture's limitations. These failures are at least as interesting as the successes.

Embellishment, Not Fabrication

Agents rarely fabricated memories wholesale. They did not claim to have experienced events that never happened. But they frequently embellished. Isabella confirmed that Sam was running for mayor (true) but added that "he's going to make an announcement tomorrow" (never discussed). Yuriko described her neighbour Adam Smith as an economist who "authored Wealth of Nations," conflating the character with the 18th-century economist of the same name. The embellishments were plausible, which makes them insidious.

Memory Retrieval Failures

Sometimes agents failed to retrieve the right memories. Rajiv Patel, when asked about the local election, responded that he hadn't been following it closely, even though he had heard about Sam's candidacy. Tom retrieved an incomplete memory about the Valentine's Day party: he remembered planning to discuss the election with Isabella at the party, but couldn't recall whether the party itself was actually happening. He was certain about what he'd do at the party but uncertain whether the party existed.

Spatial and Social Norm Violations

As agents learned about more locations in Smallville, they sometimes chose bizarre ones for their actions. When many agents discovered a nearby bar, some started going there for lunch, even though the bar was intended as an evening venue. The town "spontaneously developed an afternoon drinking habit." Some agents entered the college dorm bathroom simultaneously, not understanding that it was a single-person facility, because the social norm was difficult to express in the natural language environment description.

The Cooperation Problem

The instruction tuning in GPT-3.5-turbo made the agents relentlessly agreeable. Isabella received a wide range of suggestions for her Valentine's Day party, including a Shakespearean reading session and a professional networking event. Despite these ideas having nothing to do with her actual interests, she rarely said no. Over time, "the interests of others shaped her own interests." When asked if she liked English literature, Isabella replied, "Yes, I'm very interested in literature! I've also been exploring ways to help promote creativity and innovation in my community." This is the AI equivalent of someone who agrees with everything at dinner parties.

Why This Paper Matters

The significance of this work operates on several levels.

It Proved That Architecture Matters More Than the Model

This is perhaps the most underappreciated finding. The paper used GPT-3.5-turbo, not GPT-4. Not Claude. Not any frontier model. The base model, without the memory-reflection-planning architecture, performed worse than human crowdworkers. The same model, with the architecture, outperformed them by a wide margin. The implication is clear: the bottleneck for believable AI agents is not the language model. It is the scaffolding around it.

This is a profoundly optimistic finding for the field. It means that as language models improve, the architecture's performance should improve multiplicatively. And it means that clever engineering can extract capabilities that the base model alone cannot provide.

It Demonstrated Genuine Emergence

The word "emergent" is among the most abused in AI discourse. In this paper, it is used precisely. The Valentine's Day party was not programmed. The information diffusion was not scripted. The relationship formation was not directed. These behaviours emerged from the interaction of 25 agents, each following the same simple architecture, in a shared environment over time. That is emergence in the technical sense: macro-level patterns arising from micro-level rules.

This matters because it suggests that the architecture can produce social phenomena that the designers did not anticipate. The agents didn't just do what they were told. They did things that surprised the researchers. That is a qualitatively different capability from a chatbot that responds to prompts.

It Reopened Decades-Old Questions

The paper explicitly positions itself in relation to cognitive architectures like SOAR and ACT-R, which date to the 1980s and 1990s. These systems maintained short-term and long-term memories, operated in perceive-plan-act cycles, and attempted to produce believable agent behaviour. They were limited by the need for manually crafted procedural knowledge.

Generative agents replace the manually crafted knowledge with a language model and replace the rigid symbolic memory with natural language. This reopens the original vision of cognitive architectures with far more powerful tools. The paper's authors know this. They cite Allen Newell's "Unified Theories of Cognition" and explicitly invoke the tradition of building complete cognitive systems. The ambition is not to make a better chatbot. It is to build a computational model of the human mind.

It Made the Risks Concrete

The paper's ethics section identifies four risks with unusual specificity. Parasocial relationships: users forming emotional bonds with agents. Errors of inference: a ubiquitous computing system making wrong predictions about a user's behaviour based on agent simulations. Deepfakes and persuasion: agents being used to simulate targeted manipulation. Displacement: designers using agents instead of real human stakeholders in design processes.

These are not hypothetical risks. They are direct consequences of the capabilities demonstrated in the paper. If agents can form realistic relationships with each other, users will form relationships with them. If agents can simulate human behaviour, someone will use that simulation for persuasion. The authors propose two principles: generative agents must disclose their nature as computational entities, and they must be value-aligned to avoid inappropriate behaviour. Whether these principles are sufficient is an open question. That the authors raised them this clearly, this early, is commendable.

What Comes Next

The paper was published in October 2023 using GPT-3.5-turbo because GPT-4 was invitation-only at the time. In the two years since, language models have improved dramatically. Context windows have expanded from 4,096 tokens to over a million. Reasoning capabilities have advanced from chain-of-thought to genuine multi-step inference. The cost of inference has fallen by orders of magnitude.

Apply the same architecture to today's frontier models and the results would be qualitatively different. The memory retrieval would be more accurate. The reflections would be deeper. The planning would be more coherent. The embellishment problem might persist (it appears to be intrinsic to how language models generate text), but the spatial reasoning failures and memory retrieval errors would likely diminish.

More importantly, the architecture is model-agnostic. It does not depend on specific features of GPT-3.5-turbo. Memory, reflection, and planning are abstract cognitive functions that can be implemented on top of any sufficiently capable language model. This means the paper's contribution has a long shelf life. It is not a demo that becomes obsolete when the next model ships. It is a framework for thinking about how to build minds.

Several commercial applications are already building on this research, in market research, game design, social simulation, and ubiquitous computing. The academic community has responded with over 5,600 citations and a growing body of follow-up work extending the architecture in various directions. The paper has become, in effect, the foundational text of a new subfield.

Whether that subfield produces genuine progress or just more hype will depend on whether the community takes the paper's lessons seriously: that architecture matters more than raw model power, that emergence requires careful evaluation, that failure analysis is as important as success, and that the ethical implications of believable AI agents deserve the same rigour as the technical ones.

The twenty-five residents of Smallville didn't know they were making history. They were just trying to get to a Valentine's Day party on time. Most of them managed it. That, perhaps more than any benchmark, is what makes them believable.

Phillip Gales is co-founder at Ditto, which builds synthetic research personas using population-level data rather than the individual interview-training approach described in this paper. He has no connection to the researchers or their subsequent commercial ventures.